The 240 kilometer long Okanagan Valley has in interesting history; plant, animal, geologically and human. The lay of the land in this region was created through multiple periods of glaciation. The most recent ice age was thought to have covered the area fifteen thousand years ago, grinding it beneath a two kilometer thick blanket of ice.

As the bulk of it melted, a large ice-dam near McIntyre Bluff, just north of Oliver remained. This blockage caused a large pool of water to form north of it, creating what is posthumously known as Lake Penticton. This body of water rose to a height of approximately 100 meters above the present level of Okanagan Lake.

The clay banks forming the visually impressive bench lands seen near Summerland and Penticton were originally deposited as a glacial silt lake bottom. Post-glacial erosion deepened the intersecting valleys, leaving a wake of alluvial fans, the land which holds the city of Penticton is one such fan.

As the last ice age receded from south to north, flora and fauna traveled up the Valley from what is now the United States. Prevailing winds brought in seeds and insects of all manner, encouraging the amazing variety of plants & animals we now enjoy. A good read is provided by the Kelowna Geology Committee’s book; Okanagan Geology ISBN 0-96997-952-5.

Although I had not considered it when I embarked on the journey which is this book, I was soon drawn into learning about the valley’s geology. While much of the lingo’ employed in hardcore geological publications is beyond my capability to fully digest, I was amazed to discover how extensively the valley has been sampled, surveyed, excavated and written up in countless mining journals.

Rock & soil sampling has been conducted in nearly every square kilometer of the valley. Those looking to strike it rich, harvest timber or graze cattle have poked and prodded the width and breadth of the valley.

Our section of the Okanagan Valley is home of the Okanagan First Nations (spelled ‘Okanogan’ south of the border) whose traditional territory incorporates nearly 70,000 square kilometers in south-central British Columbia and northern Washington state.

Okanagans (Syilx) traditionally occupied an area from the northern region, adjacent to the Rocky Mountains, near what is now Revelstoke, down to a southern boundary Lake Chelan, WA. Their western range was along the Cascade Mt. Summit / Nicola valley and the eastern boundary was Kootenay Lake.

The name derives from an Okanagan language word S-Ookanhkchinx meaning ‘transport toward the head or top end’. This refers to the people traveling from the head of the Okanagan Lake to where the Okanagan River meets the Columbia River.

Okanagan Lake and Okanagan River as well as other water systems were the traditional transportation routes of the Syilx. The Syilx Territory has eight organized districts, all speak Syilx and have the same customs and stories. They are one Nation and are now commonly called the Okanagan.

The Okanagan people have been here since the beginning of people on the land, occupying the Okanagan before the arrival of the Europeans. The language which arose from learning about the land is called Syilx and all who speak it are called the Syilx, because it carries the teachings of an old civilization with thousands of years of knowledge of living on the land.

In 1811 the first non-natives arrived in the Okanagan Valley in the form of a fur trading expedition that had voyaged north from Fort Okanogan, a Pacific Fur Company outpost at the confluence of the Okanagan and Columbia rivers. Within a decade traders established a route through the valley between the Thompson River region and the Columbia River for transport to the Pacific.

This route lasted until 1846, when the Oregon Treaty laid down the border between British North America and the United States west of the Rocky Mountains on the 49th parallel. The new border cut across the valley, so in order to avoid paying tariffs, British traders forged a route that bypassed Fort Okanogan via the Fraser Canyon, following the Thompson, Nicola, Coldwater and Fraser rivers to Fort Langley instead.

Scottish botanist David Douglas also traveled through the area in the early eighteen hundreds. Most locals are familiar with his legacy of nomenclature, as it appears throughout our region in the form of the Douglas fir. Other plants bearing David’s surname include Douglas maple, Douglas spirea, Douglas water-hemlock and Douglas aster.

Hired by the Hudson's Bay Company to do a botanical survey of the Oregon region, David traveled four years and nearly 12,000 kilometers of the north-west, cataloging and collecting samples along the way. Imagine trekking 12,000k through trackless wilderness without Gore-Tex, Kevlar or Vibram soles!

When the Oregon Treaty partitioned the Pacific Northwest in 1846, a portion of the nation remaining in what became Washington Territory reorganizing under Chief Tonasket as a separate group from the majority of the Okanagan Nation whose communities remain in Canada.

Reserves were established in the early 1900's. The Okanagan people opposed the establishment of the reserves without first having negotiated a treaty. Today the Okanagan people still believe that the land is theirs, as no treaty has ever been negotiated.

The Penticton Indian Band has the largest reserve area in British Columbia with its main residential community adjacent to the City of Penticton. It is the traditional home to approximately 950 members on a land base of 46,000 acres. Reserve lands are the communal property of the members and as such are not part of the crown or public lands. They should not be entered or trespassed on without permission of the Band Chief or Council.

The Okanagan Historical Society’s many publications highlight early life in BC, along with many tales of the area’s initial transportation routes. Through many hours spent reading through these excellent books, I was amazed to learn how much the white man came to rely on the various native tribes in each area they entered.

Many of the diarized stories retold in the OHS publications describe how time and time again, the native populations came to the rescue of the white man; be it for directions, food, shelter or advise; oftentimes ‘all of the above’.

Activity in neighboring valleys also shapes the demographic of the Okanagan. In the eighteen fifties the gold rush began southeast of Penticton. This era witnessed the arrival of more than five thousand miners, most from America, which in turn prompted the construction of the Dewdney Trail as a transfer route for goods.

The Dewdney originally ran from Hope BC to Wild Horse Creek, near Fort Steele and you can still recreate on sections of it throughout Kootenays. As a great deal of copper and other ores were being mined, the Kettle Valley Railway was built in order to expedite the transfer of these commodities so that smelter traffic would remain in Canada, instead of heading for America.

There were no actual roads in the Okanagan Valley in the early 1800s, the only trails in the area being those created by First Nations people.

White-man’s version of roads and trails began with the Hudson’s Bay Fur Brigade Trail, also known as Okanagan Brigade Trail; one of the earliest commercial routes into the Valley. It ran from Fort Vancouver, in what is now the state of Washington, along the Columbia River, carrying on through the Okanagan Valley up to Fort St. James.

It was called the Fur Brigade Trail because the route was used to take supplies and trade goods from England to the fur trappers in the interior. Supplies going north included food, dry goods and tools. Trade goods included guns, blankets, pots & pans, and other items; in exchange for the First Nations people’s for furs.

Hudson’s Bay employees traveled by boat on the Columbia River from Fort Vancouver to Fort Okanogan. They could also travel on the Fraser River from Fort Alexandria to Fort St. James. However, the middle section, from Fort Okanogan to Fort Alexandria, could not be traveled by boat, so an overland trail was needed. This overland portion of the Fur Brigade Trail was very rough when the fur company started using it.

The trail followed existing First Nations trails that were oftentimes nothing more than what we now refer to as singletrack. The Hudson’s Bay Company hired Tom McKay to cut the overland portion from Fort Okanogan to Kamloops. The trail had been in use for several years, but McKay made it much easier to follow.

Twice a year, two or three hundred pack horses and men would use the trail to take goods north and bring furs south. The fur trade route came to an end when the Company stopped using the Okanagan portion of the Fur Brigade Trail between Kamloops and Fort Vancouver and instead, furs were brought south down the Nicola Valley to Hope and then on the Fraser River to Vancouver. However, in the Okanagan, the trail continued to be used by miners, missionaries, and other travelers.

In fact, Father Pandosy, the first white settler in the Kelowna area, traveled on the Brigade Trail for part of his trip between Colville WA and Kelowna, before establishing his mission in Kelowna. The trail was so well used that even today there are sections on the west side of the lake where the trail remains visible.

The information provided here was culled from a wide variety of historical literature. I realize that this isn’t the kind of information which usually appears in a trail guidebook, but I felt it important for people to grasp the history of the area’s land and people.

Those of you interested in learning more about the valley’s history should visit your local museum and library. There you will find, among other things, the Okanagan Historical Society’s 72-volume Annual Report, a collection of stories and histories of Okanagan personalities, institutions and events. A searchable index may be perused on their website

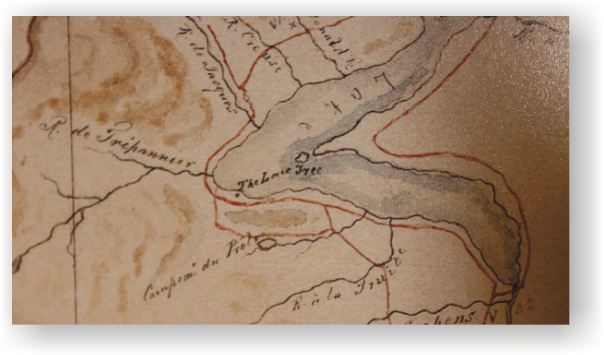

Click the header image in this chapter for a better example of the historic Anderson Map', circa 1867.